"You Are How You Move" : A Crash Course in Mechanotransduction

This comic from Bliss demonstrates mechanotransduction in action- our day to day movements affect our body! How does your cell phone/ipad/screen time affect your head and neck?

As I move into the second year of coursework for my training with Katy Bowman, I thought it might be nice to address an issue that I've alluded to but not directly written about: mechanotransduction. As words go, it may not be familiar, but as a concept, you will certainly understand it. We all know on some level that the way we "exercise" affects the shape and function of our bodies, but mechanotransduction refers to the "the conversion of movement input to biochemical processes" (Move Your DNA, pg 10). All of your movement choices, i.e., shoes, walking, how you sit, how you play an instrument, how you stand, how you exercise...these are cellular inputs into the body, meaning that your body is constantly responding and adapting to this information on a cellular level. We know some of this from experience- sitting casts our body in certain shapes and habits, whether or not we intend them. So does playing an instrument, wearing high heels, wearing misfitting shoes, constantly leaning to one side, and so forth. We usually think of this in regards to exercise, which for most people is 5 hours a week of intense vigorous activity, compared to 107 other hours a week that people are often stationary. (Assuming average person sleeps 8 hours a day and is doing things the other 16 hours a day, times 7, minus 5). Yet, what about those other 100 plus hours a week of movement or lack thereof? It's important to not just look at exercise, but look at one's whole week of movement to see what habits lie within.

The way we hold our instruments causes constant adaptation in our bodies. A lifetime of poor neck positions may result in undesirable structural adaptations!

Katy Bowman discusses all of this eloquently and efficiently in her book, Move Your DNA, and really delves into loads, but here are some of the factors to look at when thinking big picture:

1) Frequency: how often a certain shape is adopted

2) Magnitude: amount of force applied

3) Location: where force was applied, what structures are most affected

4) Duration: how long action was assumed

So for example, when we talk about practicing and increasing practice time to allow tissues to adapt, we're looking at these four factors, amongst others. If someone has been practicing a half hour a day over the holidays, and then goes back to full time symphony work of 3-5 hours a day of playing, that's a huge increase in frequency, magnitude, and duration, meaning that the tissues won't have much time to adapt in a healthful, sustainable way. If someone rarely wears high heels, and then wears them for a whole day, that's a huge increase in all of those factors as well which might result in foot, knee, hip, or back pain.

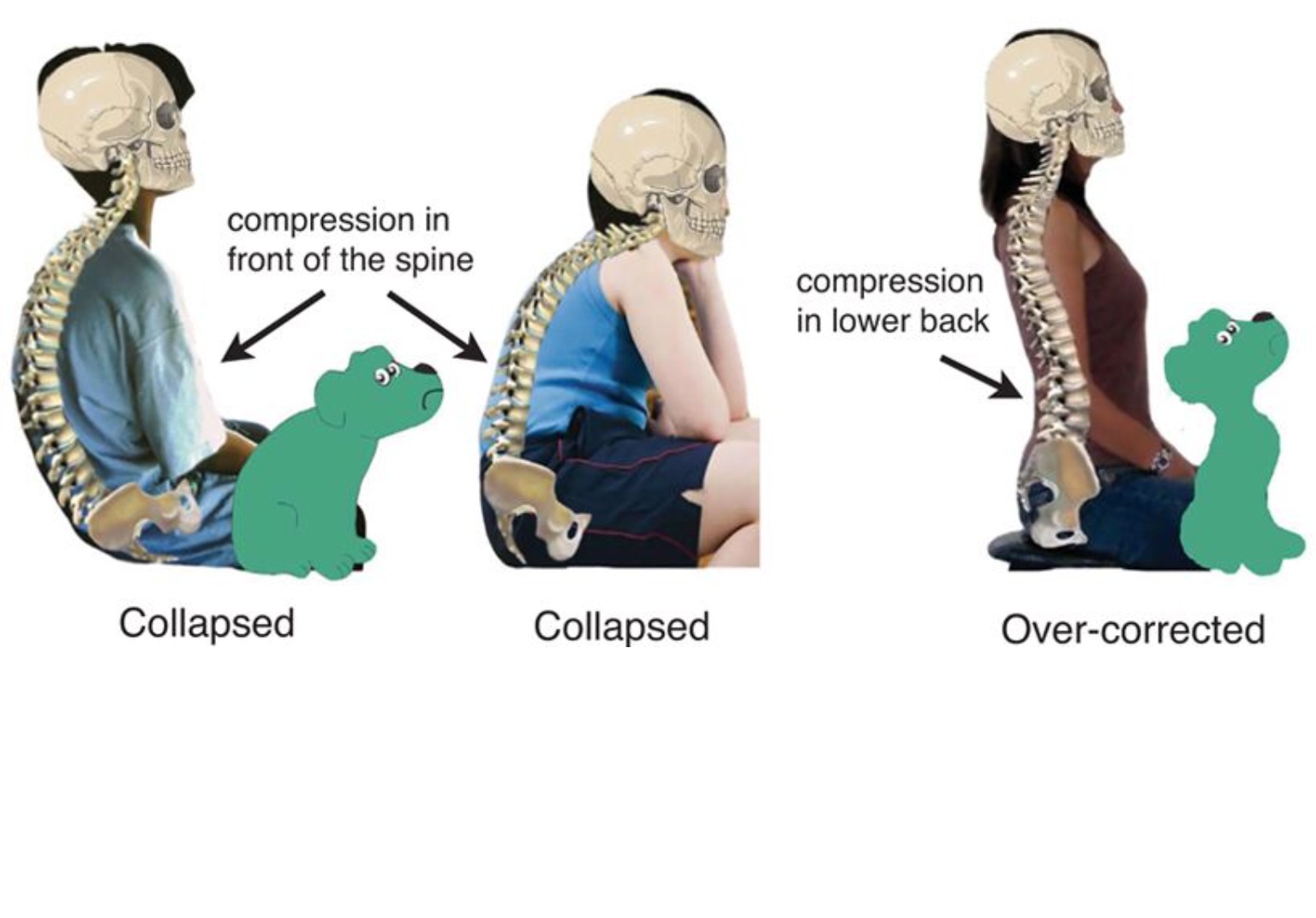

A lifetime of sitting in the collapsed positions on the left can create undesirable structural adaptations as well. Image from "Sad Dog, Happy Dog" by Kathleen Porter.

Many of our modern ailments are diseases of lack of movement and mechanotransduction- a lifetime of constant sitting will cause certain muscles, fascia, and bony structures to adapt in ways that we may not want, which can result in long term damage to the body. Many of the ailments I've discussed in the last two years are simply a result of your body processing the movement input you've given it: a lifetime of head forward posture and hyper-khyphosis will change the upper spine, years spent indulging in impractical footwear affecting the knees, spine, hips, and more, and for many of us, less than ideal ways of playing our instrument can result in negative adaptations as well. This process of converting mechanical input into cellular adaptation is precisely why moving better, gaining awareness, and self-care is so important. By the time your body is injured, you've sent it years of poor movement patterns, so why not retrain earlier and make positive adaptations to your structure? In regards to music, most of us practice significantly more than we move- it's just practical math. If someone practices an instrument 2-3 hours a day (that's a conservative estimate) for 20 years, that's probably much, much more than they exercise. If someone is a massage therapist for 4-5 hours a day for 10 years, the shapes they assume while practicing bodywork will make a greater cellular deformation. (Also, If someone practices yoga one hour a day, every day, that still doesn't account for the quality of movement in rest of their life! Yoga is not the only movement your body needs!) Now none of this has to do with the current mass media model of exercise, which is work out hard+burn calories=great looking body. This model is looking at how your body moves, not how it looks, not how thin/fat/muscular you are, but range of motion, pain, tissue health, etc. Although weight is one factor of determining health, it is by no means the only way to evaluate. (And for those of who are movement instructors or have a regimented training/workout process, how is your exercise affecting your tissues and what about the movement habits you adopt for the rest of the day, week, and life?)

So the question I leave you with now is how do you move?