Shoulderstand, or Just Because A Teacher Suggests A Pose Doesn't Mean You Should Do It

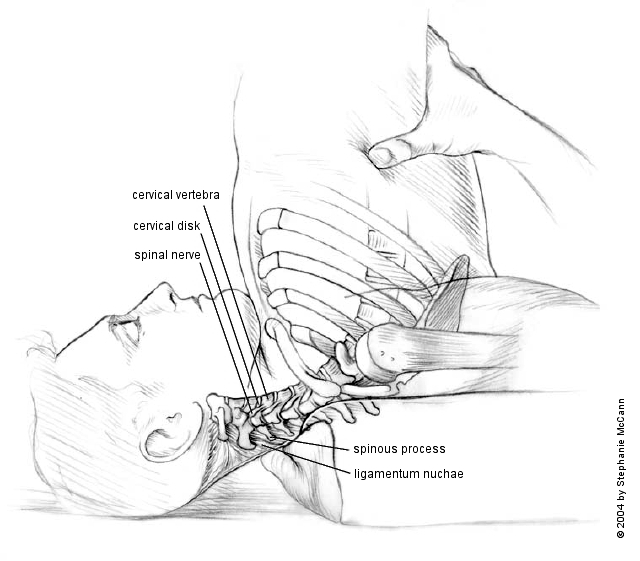

This is an anatomical cutaway of shoulderstand with the the hands and forearms on the ground. (Note the breast tissue is defying gravity and not descending towards the earth.) I can't remember where I found this, so I'm sorry!

If you're not a yoga or pilates person, this particular blog post may be of little interest to you. My apologies. For everyone else, let me continue. I rarely teach full shoulderstand in a yoga class (or full jackknife in pilates), especially not to musicians. I've mentioned this before, but I realize that I should give some thoughtful explanation to some of my yoga musician friends who may be wondering what I'm thinking.

First of all, yoga is not inherently beneficial, meaning that not all yoga poses are equal, and not all yoga postures will be suitable for everyone. There is sometimes a view that yoga cannot harm people, which is frankly a lie. People get injured in yoga classes, teachers get injured in yoga classes, and like any movement based activity, certain movements are riskier than others. With that in mind, let's look at musicians as a general population and some of their tissue issues.

-We often have neck pain and neck injuries from Repetitive Strain and decades of instrumental study.

- We often have limited ROM in our shoulders, weak shoulders, or shoulder pain.

Iyengar was one of the most famous teachers of the 20th century who touted this pose as the most beneficial, as well as headstand. He is also built like gumby, and his lifestyle and body is not similar to most of my musician and yoga realm colleagues. He also does not have female breast tissue, otherwise he might have reconsidered the suffocating detriment of this pose.

-We have often accepted a certain amount of pain from musical study as normal, which means we might not be able to detect destructive pain signals in weight bearing situations.

-We have spectacular proprioception of hands, jaw, fingers, embochure muscles, etc, but don't necessarily have large muscular/joint proprioception.

- We often have tucked pelvises and forward head position from sitting in a slouched chair for 6-8 hours a day.

I'm sure you get the idea, so let's go back to shoulderstand. I bring this posture up because it is often touted as the most beneficial posture ever, and its risks are typically ignored, or at least an afterthought. Here are some of the yoga articles promoting it's benefits: 10 reasons to do a shoulderstand every day, Shoulderstand: a Love Story, or another article on how to modify shoulderstand as to not overstretch the ligaments of your neck. Ok folks, let's take another look at the benefits of shoulderstand. Here are some highlights from yoga journal and the above mentioned blogs:

This is an awkward internet drawing of neck flexion.

-It circulates lymph, it's an inversion which has inherent benefits, it's excellent for thryoid disorders, it soothes the nervous system (unless you're suffocating on your own breast tissue), it's good for fat loss (I'll believe that when there's a study), and will apparently relieve symptoms of asthma.

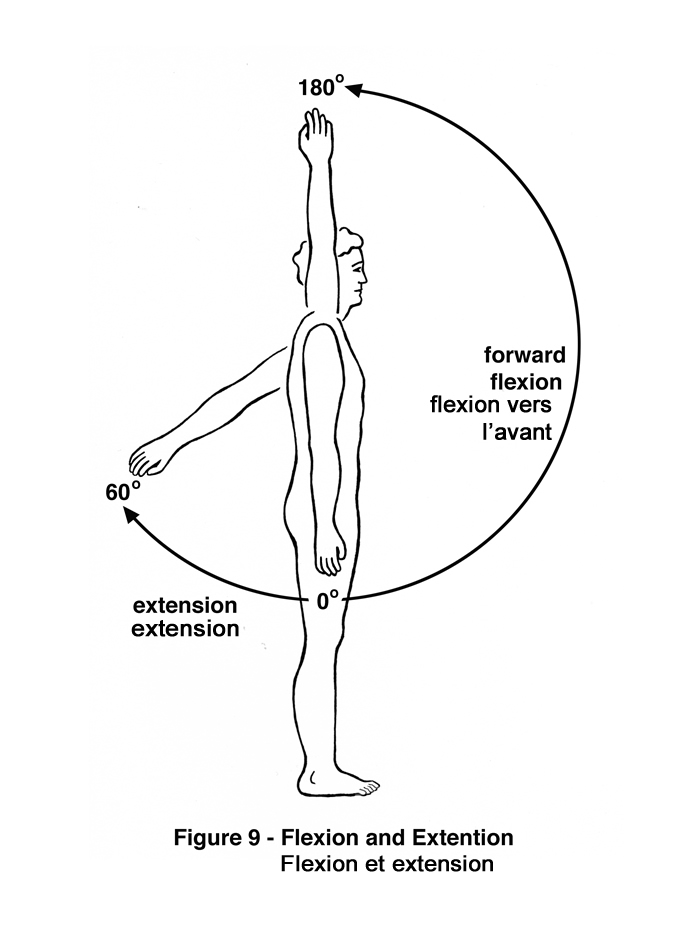

Sorry for the cynicism, but I have always strongly disliked this posture because (suprise!) it doesn't feel great for my neck, I always feel like I'm suffocating in my own breast tissue, and I think there are better postures for musicians (and most yoga students) who already put stress on their neck ligaments and cervical spines. But I digress. There are two main actions needed for shoulderstand: full shoulder extension and full cervical (neck) flexion.

Here's the test I learned from the folks at Yoga Tune Up® which has alleviated my guilt from disliking this pose.

1. Interlace your hands behind your back. Lift your arms.

2. Do your arms end up being parallel to the floor when you lift up?

3. If you can get your arms parallel to the floor in full extension, do you distort your torso and neck?

4. Can you then also flex your neck fully to your chest with shoulders in extension?

5. If not, then why try and and invert when you'll be smooshing all your weight into your neck? Can you see why you need to be able to lift your arms to parallel? You're essential trying to make a 180 degree line between your flexed neck and your arms in order to support yourself.

"Viparita Karani" or legs up the wall for you non-sanskritters. Leotard optional.

If you can't get your shoulders in extension parallel to the floor, why are you going to turn it upside and try to force your arms to the floor when you can't do it upright? It's an impossible task! Then, add some weight and you'll just end up crunching your neck. Sounds painful, right? Simply put, most people (especially musicians) don't have the shoulder capacity to do this pose safely, and their lack of range puts a huge strain on the neck, which is already a tricky place and source of pain for many of us. Added in that many people can't do the full range of neck flexion, (i.e. chin to chest) needed here, which is why there can be problems. Why try to put yourself into a posture that's not built for your body or most bodies? Do something that makes sense for your body and your range of motion, as well as your long term health. Or even better, start practicing movements that will prepare your body for that posture (if you really want to do it). Some people can (and do) have the range of motion and strength to do this pose safely. Others don't and have injured themselves. There are lots of supposed benefits to this posture, but not at the expense of your neck, folks! Try something a little more friendly, like viparita karani, which is a gentle inversion (getting you that lymph exchange and blood flow benefit).

And here's a warning about what can go wrong in shoulderstand:

“What happens if your student forces her neck too far into flexion in Shoulderstand? If she is lucky, she will only strain a muscle. A more serious consequence, which is harder to detect until the damage is done, is that she might stretch her ligamentum nuchae beyond its elastic limits. She may do this gradually over many practice sessions until the ligament loses its ability to restore her normal cervical curve after flexion. Her neck would then lose its curve and become flat, not just after practicing Shoulderstand, but all day, every day. A flat neck transfers too much weight onto the fronts of the vertebrae. This can stimulate the weight-bearing surfaces to grow extra bone to compensate, potentially creating painful bone spurs. A still more serious potential consequence of applying excessive force to the neck in Shoulderstand is a cervical disk injury. As the pose squeezes the front of the disks down, one or more of them can bulge or rupture to the rear, pressing on nearby spinal nerves. This can cause numbness, tingling, pain and/or weakness in the arms and hands. Finally, a student with osteoporosis could even suffer a neck fracture from the overzealous practice of Shoulderstand.” -Roger Cole

If you DO want to practice shoulderstand, here are some things to think about: do you have the necessary range of motion to perform it? How often do you practice the pose, and for how long? If you need to improve certain ranges of motion to perform the pose, are you working on those in your daily life (like improving shoulder extension)? Since I've started teaching pilates in the last few years, I've really enjoyed the different regressions and different approaches to a similar movement in the pilates repertoire, jackknife, which asks for less extreme ROM in the shoulders and spine, as well as a much shorter hold.

Ouch! Believe me yet? Want to read more?: I like this article from Smarter Bodies and the ongoing work from Matthew Remski re: yoga injuries and asana.