Teaching To Multiple Intelligences in the Music Lesson

One of the early covers of "Frames of Mind."

I was thinking about Howard Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences last week when I was teaching a kids' yoga class at the library, and then I realized that I should probably share my thoughts on the blog. We often think of ourselves as music teachers, meaning that we are primarily teaching the skills needed in music. This is true to a degree, but when you think about multiple intelligences and how they relate to the learning space (private lesson, group class, etc.) you realize that you're teaching a whole set of different social-emotional and cognitive skills to a child in a music lesson. Knowing the M.I. theory can not only help you when you're at a loss of what to do, but can also make lessons, group classes, and ensembles more diverse and stimulating.

First off, what is the theory of multiple intelligences? Well, it's not quite the same of learning styles, which you may have heard of: visual, auditory, and kinesthetic, but instead is a reflection of Gardner's believe that people are not either smart or not, but instead have a series of different intelligences in different areas. Before his work in the 1980's, children were typically tested on an IQ test, which almost exclusively measured verbal/linguistic and math/logic skills. Those are obviously excellent skills to have, but do not represent the full set of intelligences a child or adult might possess. Howard Gardner, a social psychologist, published his first book on the subject in 1983, called "Frames of Mind." I've read pieces of it, but I imagine it would be a great read if you want more information on his work. In it, he detailed 8 different areas of intelligence, which definitely show up in the musical learning space.

1. Verbal Linguistic: children are highly verbal, strong in reading, enjoy writing and stories

2. Math/Logic: children enjoy identifying patterns, looking at abstract issues, deducing relationships, problem solving and reasoning

3. Spatial Intelligence: children create visual spatial representatives of the world (maps, charts, drawings, etc.). Children additionally enjoy mazes, puzzles, art, etc.

4. Musical Intelligence: children have an awareness of sound, melody, and have pitch and rhythm skills. (Many music students you teach will have this intelligence, and many won't!)

5. Bodily Kinesthetic: children enjoy using their body to move, have good hand eye coordination, enjoy physical activities. (This is a big piece to learning an instrument-fine motor and gross motor skills!)

6. Interpersonal: children work with other people on a task, cooperating well and communicating. (Extroverts are not necessarily good at this, because they sometimes steamroll others' ideas!)

7. Intrapersonal: understand one's own emotions, goals, strengths, weakness, and can work alone well.

8. Naturalist: understanding the natural world, having an interest in plants, animals, environment.

Now that you have a basic understanding of the intelligences, you can probably see that the study of music covers 7/8 of intelligences. (I haven't quite figured out how naturalist applies to music, except in the understanding of how instruments are made.) Let's look at how to engage students in these different areas of learning in a music setting.

1. Visual/Linguistic: Have students write a story about a piece. Have students pick adjectives to describe the types of sounds they want to make. Teach students words to correlate with rhythms. Have students research the composer and piece and write or speak about it. Invite students to write a letter to a composer or performer (living or deceased) and talk about a piece or performance they like. Keep a practice journal detailing daily habits (also intrapersonal activity). Ask a child to think of music to go with a story that they like.

Believe it or not, this is a drawing I did, circa 1992 (age of 6 here, folks). I remember going to see the Nutcracker and then being asked to draw pictures of what I saw. Children often love to draw characters from performances, songs, shows, etc., so invite them to draw things related to what you're working on! Draw Mozart! Draw a violin! This is both a spatial intelligence project and can be a verbal/linguistic, if you ask them to write and respond as well.

2. Math/Logic: Identify patterns in music, whether sequential, pitch related, or rhythmic. Create a rhythmic challenge for your students, and then ask them to create a rhythm for you to copy, either aurally or written down. Explore irregular rhythm patterns and additive rhythm in other cultures. Have a student understand and explain fractions through music.

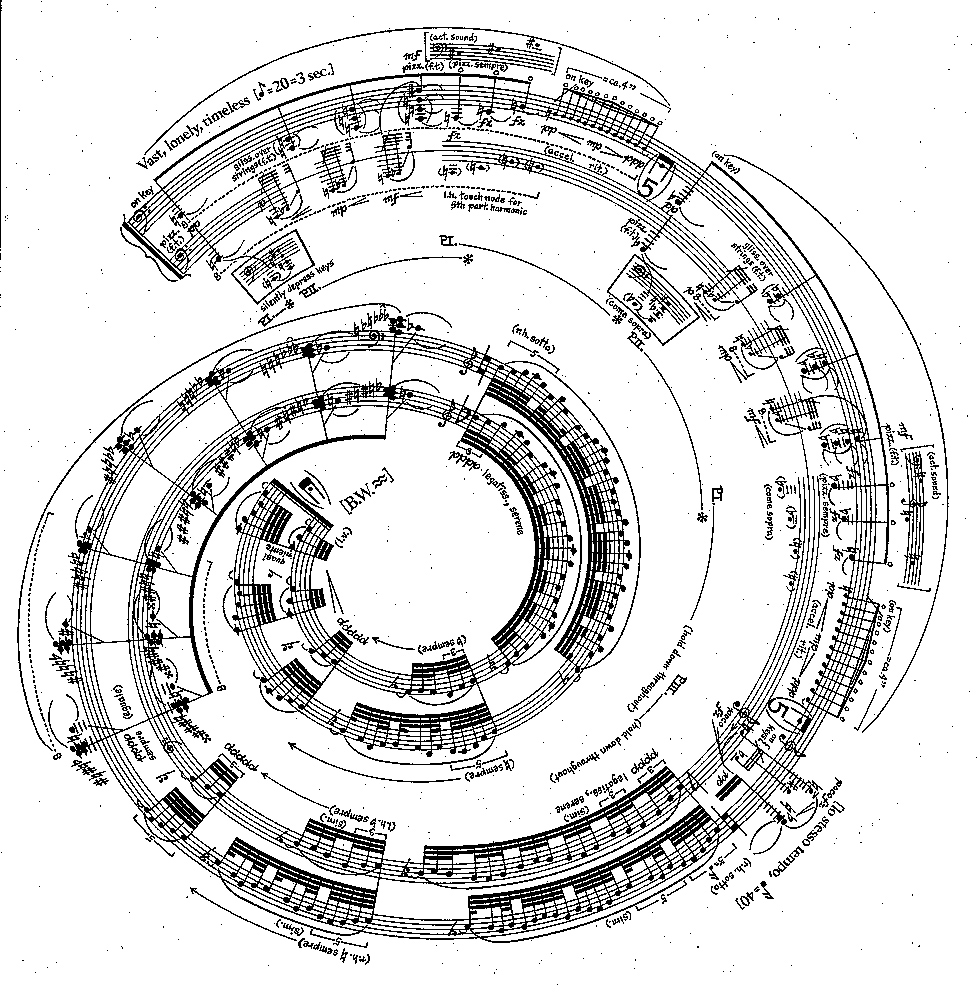

Image from George Crumb's "Makrokosmos"

3. Spatial: In my understanding, the act of reading music is in fact a spatial and visual intelligence. Music notation is like a new language and new set of symbols, so having a child learn to reproduce those symbols (key signature, notes, staff, etc.) is a spatial activity. Challenge a child to create their own piece or snippet of a phrase by writing out the symbols to their liking. Invite a child to draw a picture about a piece or composer. Have a child look at a book of art and pick a work that suits the piece they are studying. Show children the different ways that composers notate music, especially in the twentieth century. See if children can find ways to understand new and more abstract ways of notation. Invite them to create their own notation system.

4. Bodily-kinesthetic: Music engages kinesthetic learning, and often coordination is a difficult skill to acquire in terms of fine motor skills. For example, a five year old studying violin may have difficulty moving individual fingers, or holding the bow correctly. (They are also just learning to write and hold pencils and crayons, so be patient!) Bring in other movement activities to help the child develop more fine muscle coordination. Songs and games involving finger movement can help, learning basic sign language can help hand coordination, trying different instruments can be helpful too. Invite a kids' yoga or dance teacher to a group class and look at large muscle movements, or teach a 5 minute warmup before a lesson for shoulders, back, and neck. Ask students "where they feel the stretch." Other fine motor activities can be making finger pincers like a crab, picking up marbles with toes, making the bunny ear bow grip, etc.

Bodily-Kinesthetic learning can take place in dance classes, sports, kids' yoga...lots of different places! Supporting children in understanding their bodies can help them play their instrument, as well as create a lifetime of healthy habits. Photo from my kids' class from last week, courtesy of Michelle Garduno.

5. Interpersonal: Group classes and chamber music is a great way to explore interpersonal skills. Having children learn twinkle variations together and perform them without you leading themis great practice, especially if you pick different children to lead. Have older students play scales in unison, focusing on matching bow distribution, sound, volume, etc, of a leader, and then switch leaders. One of my teachers made studio class a chance to do group scales with a metronome, i.e. in a triplet, three people are assigned to each grouping, alternating G-A-B... between the three of them as they go up and down the scale. Obviously, chamber music on a more sophisticated level demonstrates these skills and develops them in young adults.

Here I am in Wyoming with a girl and her mom, who have to move together, and I respond sonically to their movements. Think of it as bodily-conducting. It's fun, it's kinesthetic, it involves group participation, and it's goofy.

6. Intrapersonal: Music is largely an intrapersonal (and individual) practice. Students who like to practice by themselves and self motivate without parental insistence are great, but often rare. The skills of spending time with oneself and one's instrument, looking at how one practices, looking at what one practices, etc., is a difficult set of skills to develop. Ask students reflective questions like "what did you do to make this better," "how can we practice this," etc., and for more advanced students, have them keep a practice log. For an adult student or yourself, keep track of strengths, weaknesses, goals, etc., and use auditions and performances as a way of monitoring your own progress.

7. Musical: This is the intelligence that you have been trained to teach, and that truly encompasses all of these other intelligences (aside from naturalist). From learning how to read music and understand rhythm, to holding an instrument, and learning how to make sound, you probably have lots of ideas of how to teach music in many different and creative ways already.

Finding connections between music and these other intelligences will not only make lessons more interesting for you (especially if you run out of ideas) but will also engage students in new and diverse ways. You can also begin to look at students and see where their strengths lie- not only in the musical intelligence realm, but in the other intelligences, and see how your teaching can support them. Perhaps you have a young child who is not verbal, and their parent talks for them often. Invite them to express themselves in other verbal ways, and ask them to read titles of songs, identify markings, etc. Even if a child is not musically "intelligent" from a young age, your teaching can support their growth, no matter what they end up pursuing as a passion, and can help inspire learning throughout their lives.