10 Things I Learned While Recovering from Reconstructive Hand Surgery

by Kelly Mollnow Wilson

I am a professional flutist, teacher, Licensed Andover Educator, wife and mother who has successfully completed the long journey of recovery from reconstructive hand surgery. I share my story here to let other injured musicians out there know that they are not alone and that it is possible to recover from a potentially career-ending injury.

The Injury:

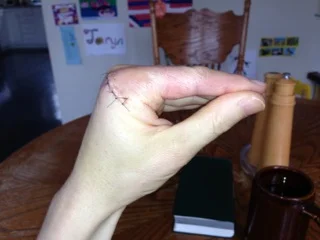

Pre-surgical splint to immobilize MCP joint and a kid version designed and built out of duct tape by my youngest child.

In the fall of 2012, I injured the base of my index finger on my left hand.The new flute I had purchased in August had a different arrangement of keys than the old flute, and this design change was causing me pain. My symptoms improved after I stopped playing this specific flute and took a month off from playing. Unfortunately, my right hand slipped off the edge of the bath tub while helping my youngest daughter one night and my left hand contacted the bottom curve of the tub with fingers hyperextended, bearing the whole weight of my body. The main point of contact was the base of my left index finger and there was an audible w “pop” from inside my hand. The eventual diagnosis was a ruptured sagittal band at the MCP joint of my left hand index finger and damage to the radial collateral ligament, which connects hand bone to finger bone. The MCP joint is the metacarpophalangeal joint or the big knuckle where the finger meets the hand. The sagittal band is connective tissue that is part of the extensor complex, goes around the joint capsule and keeps the extensor tendons tracking over the middle of the knuckle when you make a fist. The extensor tendons are the ropy things you see on the top of your hand when you make a fist. They should be centered over the knuckles. In my case, the extensor tendon of my index finger was pulling towards the valley between index and middle fingers, “the valley of doom” according to my doctor and there was significant pain when lateral force was applied to the joint. For a flutist, this is a really big deal because the base of the index finger is one of three areas of support for the flute, this finger has to hyperextend and it has to operate a key that needs to be closed for the majority of the notes on flute. Conservative treatment consisting of splinting the MCP joint failed, leaving only a surgical option. My surgery was done at the end of March 2013 and was considered best possible outcome because no hardware or extra tissue harvested from elsewhere was needed to repair the shredded and stretched connective tissue. My surgeon was able to put it all back together and sent me out the door to hand therapy. [Healing My Clipped Wing chronicles the whole recovery process in weekly installments if you want more details about the specifics of the injury and the process leading up to surgery.]

First picture after cast was removed 4/3/13. Greenish tinge and the pen markings put on pre-op by my surgeon.

1) It is often difficult and time consuming to get the correct diagnosis. Four doctors were consulted before I received an accurate diagnosis. My range of motion and ability to move in directions that I shouldn’t have be able to do with the injury I had sustained made the initial diagnosis tricky. I suspect that many musicians would fit into this category. Do not stop looking for answers to a medical problem when you don’t get a definitive answer. Keep asking questions. Sometimes, it’s a matter of finding the right medical professional. Other times, the diagnosis comes as a result of eliminating things that can’t be wrong. For me, there was no neurological issue according to the neurologist, so I was sent back to the orthopedic specialists. You have to be persistent and advocate aggressively for yourself.

One of the exercise 4/9/13. Sutures still in place.

2) Hand therapy (any kind of rehab therapy) is both wretched and fabulous. Wretched: I was fortunate to have access to fantastic hand therapists, but hand therapy is not a fun thing. Therapy exercises hurt, period. My first set of rehab homework consisted of 14 different exercises, all of which need to be repeated 10 times, with 4-5 sets of the whole thing per day. Rehab started 6 days post-op, before sutures were even removed. The complete set of exercises took 75 minutes, including the ice time after and it was taking 5 hours per day. It’s incredibly frustrating and devastating to issue a movement command to a finger and have virtually nothing happen as a result. Each week, I’d go to my appointment feeling optimistic that I had improved on the week’s exercises, only to be given a bunch of new ones that I couldn’t do. Scar massage is another thing that I didn’t even know was a “thing” and involves manipulating the incision site to prevent adhesion and desensitize the nerve endings. There’s a reason they prescribe pain meds during this time - you need them to be able to do the work. Fabulous: Therapy works when you do it. There’s a reason for everything they are asking you do and if you do it, you will get better. If you want to reach your goal, you have to do the work because there is no movement shortcut.

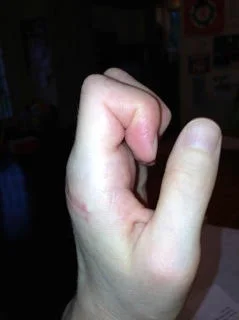

4/28/13 I can get my hand onto my favorite coffee mug, but can't yet pick it up!

3) Body mapping knowledge helps with rehab exercises. As a long time Andover Educator, I’ve taught lots of musicians how their bodies work during the movements of music making. There was not much instruction about what specific muscles in my hand where supposed to be engaged to produce the movements required by each of the exercises. When I asked the hand therapists, they would tell me, but they said that most people don’t want to know. So, I used my own experience as a somatic educator to work smarter. The first thing was to find out exactly which muscle(s) should be working for each exercise, as well as which muscle(s) should not be trying to help. Muscles are usually found in pairs, when one contracts, the other releases into length. I used the Visible Body Muscles 3D app on my iPad as well as Trail Guide to the Body by Andrew Biel and Anatomy of Movement by Blandine Germain-Calais. I went through each exercise and wrote on instruction sheet the name of the muscle, its origin and insertion points. Body maps can be continually refined and knowledge is power. Visually, I was able to direct my focus to where the muscle in question was supposed to be moving. Even if there was no movement at the finger tip, the muscle can still be working. I reminded myself continually that these exercises are whole body movements, not just finger or hand movements, and that I always needed to keep the part within the context of the whole. I forced myself to have feet on the floor, butt firmly in the seat balanced on rocker bones, leading movements with my head, and not allowing myself to contract around the injured part and hold my breath. I started doing the exercises with both hands, mirroring each other, using the good side to teach the bad side. I took my iPad with the Visible Body anatomy app to each appointment and asked many questions until I was clear about what was supposed to moving. I also needed to ask about how to know where the boundary is between “pain that’s necessary for movement” and “pain that is a signal that you’ve exceeded the range of motion for that day.” To get the most effective results, one has to work as closely to that boundary line as possible, without going over.

4/28/13 Lots of progress with range of motion and sutures finally out.

4) Waiting is hard and patience is, indeed, a virtue. It’s no fun waiting to see if your body can heal itself while you’re stuck in splint for months, waiting for the next available surgery time slot, waiting for your body to heal a surgical incision, waiting for a grown up to come home because you weren’t able to teach a preschooler to open the safety cap on the pain meds. I was released from hand therapy after 3 months because my range of motion and strength were at acceptable levels; however, I couldn’t come close to playing my flute. It was very clear that what musicians require in terms of hand usage is much more specific than the general population. Scar tissue remodels for up to two years after surgery and the therapists had nothing to offer me. Time and effort are the secret ingredients. Trust in the process even when it doesn’t proceed on your chosen time schedule. Sometimes, the “process” is hard to believe in. This seems to go against everything we know about pain: “if it hurts, don’t do it” and “leave the cut alone, let it heal without picking the scab.” With hand therapy, it seems exactly the opposite... “yes, you must move it when it hurts if you ever want to move it again” and “yes, massage the most painful spot...over and over again.”

5) The emotional impact of a injury can be just as overwhelming as the physical impact. In hindsight, I would have benefited from working with a mental health provider and, now, I always encourage that with students who are dealing with a severe injury. Here’s some of my emotional mess:

Devastation - I've spent years and years learning my art form and now I can't do it all for an indefinite period of time?

Guilt - Why should this injury be such a "Big Deal" to me when I have friends, relatives, and colleagues dealing with chronic health issues like cancer?

Anger - Why is the universe conspiring against me?

Lack of trust - So I did what the doctor and therapist said, 100% compliance with all instructions, and now I'm worse? Is the diagnosis right? Do these people know what they're doing?

Frustration - So there's really nothing I can do except wait?

Disappointment - Having to turn down and cancel professional engagements is hard. Accidents happen and people get hurt; however, we all work hard to get the gigs and who wants to have to cancel? When will the next opportunity come around?

Financial stress - Luckily for me, my ability to feed and clothe my family doesn't depend on my ability to generate an income. This is not so for other musicians.

Self map issues - If I've mapped my self as a flutist, what I am without the flute? If I'm a band director, what am I without a band? How can I be a musician who can’t make any music?

Impatience - I know how to regain my playing skills, once the _____________ (insert injury) heals. Come on, already!

Lack of trust in my own judgment - How can I teach other musicians how their bodies work when I hurt myself on my own stupid flute and bathtub?

Loss of independence - I hate having to ask for help, but I need help to floss my teeth, zip my pants, cut my food and put ponytails in my kids’ hair.

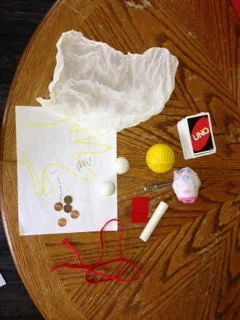

All of the my toys for hand therapy.

6) It takes a team. In my case, I worked with a hand surgeon, hand therapists, acupuncturist and naturopath physician, Alexander Technique teacher, physical therapist, Feldenkrais practitioner, a medical massage therapist, several chiropractors, and a NeuroKinetic therapist. They are all masters of their own area and helped me heal various aspects of my injury. No single modality has all the answers. I also had my home team - my husband, family, and kids all working together to make everything go as smoothly as possible. My older child took over cutting my meat and vegetables at dinner time and my youngest was the pepper mill grinder & salt shaker.

4/20/13 Hanging by left hand from kids' bar on playground.

7) Dysfunctional patterns can exist for long after the need for them has passed. It took well over a year for me to eliminate the dysfunctional holding pattern on my entire left side. I knew that this pattern was there and I took steps on my own to address it, yet I needed the help of the professionals listed in #6 to eliminate the pattern. The hand therapists only care about the hand in isolation, they’re not interested in the rest of the arm or body. The hand surgeon only cares about the stability of the structures. Hand surgeons are amazing, being able to go into a incredibly complicated area and fix what is broken without damaging anything else. They all did their jobs well, but I still had a gimpy left side. My left arm was pulled in and up towards my body, the universal “broken arm/hand” pose. I would startle immediately if anybody made a sudden movement towards my entire left arm. I had a panic attack at the 3rd grade chorus concert because people were too close my hand in the crowded bleachers at the school. I lost muscle mass in my left arm and torso, which is not surprisingly with the 5 months of restricted activity prior to surgery and the whole rehabilitation process. I returned to weight training and got a pull-up bar for Mother’s Day to work on both grip and upper body strength. I did lots of constructive rest, inhibition and redirection to convince my nervous system that my hand was ok. And it is.

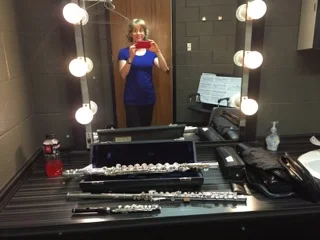

Pre-performance 4/25/16

8) Relearning to play is both humbling and exhilarating. When I was finally cleared to begin with the flute, my doctor said “You can play as long as you don’t go crazy and stick with baby stuff, not notey flute stuff with low load/high frequency.” This translates to a few minutes a day at first and I had to start with 1 and 2 minutes at a time. Everything had to be relearned. Interestingly, when doing a Skype lesson with a trusted colleague, her first statement was “Do you know what you’re doing with your head?” Of course I didn’t, because I was focused entirely on my surgical site. This is one of the tenets of basic Body Mapping - music making is a whole body activity, always, and I was focusing all of my awareness on a specific part at the expense of the inclusive awareness of my whole body. The desire to get the flute back in my hands was so high, just like when I was a 4th grader and couldn’t wait to get that shiny thing in my hands. I used to be a technical whiz kid, the faster the better. Now, I have to learn the notey stuff slowly and appreciate what countless students of mine have had to deal with when learning fast passages slowly. I have to be smarter about how I practice because I don’t have unlimited hours. My practice window is about 90 minutes or less with breaks every 10 minutes or so, on a good day. Being more mindful and efficient is always beneficial. This is another area where my knowledge of Body Mapping was an advantage in relearning the movements that I need to play my flute, as well as being aware of and eliminating the movements that don’t help.

Flutes onstage 4/26/16

9) Modifying the instrument isn’t cheating. Pre-injury, I would have classified myself as a purist. I thought that if people were using their bodies well, then there was no need for any external modification on the flute. I’ve since changed my tune! When I first returned to playing, I started on a vertical headjoint, loaned to me by a very generous individual and it allowed me to play without any contact of the base of index finger with the flute tube. Since then, I’ve had many different things added to my flutes including a key extension, which raises the height of the left index finger key and also makes it closer to the others, a rubber pencil grip sliced in half or a Dr. Scholl’s corn pad stuck onto the flute tube as padding, a right hand thumb support made of cork which allows more of the flute weight to go into my right hand thumb (made by Alexa Still at Oberlin), and a custom foot joint key cluster done by John Lunn. Everybody is different and if modifying the instrument makes it easier for you to do what you want to do, then do it. What works for one person might not work for the next person. Who cares what it looks like?

10) I’m a better, more compassionate teacher and human for having had this experience. I wouldn’t wish it on anybody, but I now empathize with musicians who have pain and injury. I understand the terrible feeling of frustration and emptiness that goes along with not being able to make music. Every person that you meet has a story, has things going on in his or her life that you know nothing about. I’m more efficient in my practice and more respecting of my physical limitations. I can stand up and say that this will not last forever and you’ll get through it, I hope. I can say to injured musicians that they are artists and will always be artists even if they can’t play their instrument or sing right now. My injury was not fun, but it was something that could be fixed and I was so incredibly fortunate because sometimes there is no easy fix. It seems utterly ridiculous to write that surgery is an easy fix because no part of this entire process was easy. I am thrilled to say that I’m back performing with the Aella Flute Duo, I’m just finishing up a semester-long Intro to Body Mapping course at Oberlin Conservatory and, just last week, I had a gig as part of a flute and percussion duo performing for dancers which required me to play alto flute, C flute and piccolo for the first time since my surgery. My professional interests have changed as a result of putting myself and my hand back together with lots of help from various professionals. Specifically I want to be able to help other musicians directly through manual therapy and will be starting a massage therapy program in the fall with the eventual goal of becoming a NeuroKinetic therapist. My goal is to be able to teach movement and awareness, prescribe corrective exercises as needed, manually release muscle tension and scar adhesions, and correction muscular imbalances to allow musicians to do what they do without pain and restriction, as they strive to realize their full potential as musicians.

About the author:

Kelly Mollnow Wilson, a Licensed Andover Educator since 2007, currently teaches privately and is a freelance flutist in Northeast Ohio. She has presented Body Mapping workshops at Cleveland Institute of Music, the International Flute Symposium at West Virginia University, and at the National Flute Association Conventions in 2006, 2012 and 2014 and is currently teaching Body Mapping at Oberlin Conservatory. She is a founding member of the Aella Flute Duo (www.aellafluteduo.com), which will be performing at the NFA Convention this summer in San Diego. Kelly has nine years of teaching experience in the instrumental music department of the Wooster City Schools in Wooster, OH and is the lead author/flute author of Teaching Woodwinds: A Guide for Students and Teachers. See http://wilsonflute.com/ for more information.